![]()

Forty Years Later with two Old Testament Dudes

On Dewey Whitwell's Knee, I Consider My Second Amendment Rights

![]()

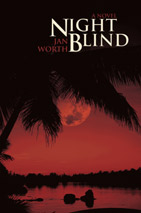

"Jan Worth published her great novel Nightblind herself (with iUniverse) and thank goodness she did. She worked on it for about thirty years she says in the Acknowledgements.

Worth’s book is splendid and delightful, wise and witty and rich. Twenty times better, say, than something like Eat, Pray, Love...." (Read the full review...)

![]()

Essays > Ed Custer's Circus Parade: Joyful Study in Anticipation.

Edwin Custer is a quiet man, and on entering his beautiful Craftsman-style house on Crapo Street one hears just the subtle bubbling of a small fountain and low-key jazz.

It’s a space obviously devoted to the pleasures of the eye. In every corner and on every shelf are paintings, ceramics, sculptures, drawings, shells, stones — all lovingly chosen and arranged, many in earthy browns, serene grays and gentle pastels. On the walls among the large oil paintings are many of Custer’s black and white photos that for decades have provided covers for East Village Magazine.

It is, he says, “serious work,” the art he’s created over 40 years, a visual history of not just his own life, but also the architectural and riparian beauty of Flint. The paintings on the walls are thoughtful, sometimes mischievous interpretations of Riverbank Park, the pressed bronze lions’ heads of North Bank Center, the Masonic Temple, the Michigan School for the Deaf and numerous East Village porches and rooftops.

And then, there’s something else.

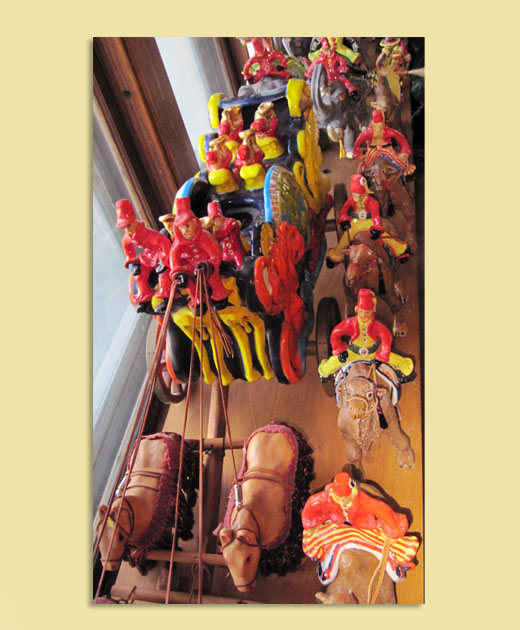

In the wide front window of his living room, on an 11-foot-long board atop a radiator, is a piece I can’t look at without laughing and muttering “Wow.”

It is, of all things, a circus parade — a joyful, whimsical, flamboyant and frankly, downright zany 30-piece ceramic extravaganza.

That exuberant, seemingly incongruous piece is what prompted me to write this column, the first time in its 33-year history to feature one of the family behind East Village Magazine. I’ve known the Custers off and on for 28 years, though I didn’t write for the magazine until three years ago. But still, I had to gently force Edwin to let me interview him.

There’s a news hook to justify his venture out from behind the scenes. Custer’s circus opus, his gaudy parade, will be displayed publicly for the first time this month at Buckham Gallery, 134 W. Second St.

Custer, 66, is a retired planner and project manager for the city of Flint. He worked to improve the urban landscape, burying wires underground at the Flint Cultural Center, reforesting parkways with street trees and fighting for residential neighborhoods.

Born in Detroit, Ed and Gary Custer came to Flint with their parents who migrated here from Missouri for work in the early ‘50s. His father Lloyd worked for years in Buick’s Suggestion Department, sorting through, selecting, implementing and rewarding employees’ ideas. His mother was an elementary school teacher at Parkland, Cook and Walker schools. Lloyd and Nola bought a house on Avon Street where the boys grew up and which they still own. Ed married a Flint girl, Casey, and they have two sons, Nic and Andy.

Art was Ed’s first love, and art remains the thread weaving through his life. After a bumpy start at the University of Missouri and two years at Flint Junior College, where he was strongly influenced by art professors, Robert Devore and Doug Warner, he surprised himself by getting accepted into the bachelor of fine arts program at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. He stayed for a master of arts. Then, after 3 1/2 years in the Army with time in Vietnam, he went back for a master’s in landscape architecture.

But the circus?

It started with his father, for many years a local Shriners clown, especially after he retired from Buick. Custer watched his father perform and as a kid went to the circus every time it came to town.

“I enjoyed the idea of the circus,” Custer says. “Circuses have a magic to them.”

But then he found himself delving deeper, exploring the idea that “the circus parade was the culmination of an event — another event really — the prelude to the circus.

“I was interested in how much preparation there was — setting up the Big Top, that big tent. And then I started thinking about how the circus got to town.”

For many years, he notes, circuses traveled across the country in trains. When they got to each town, to draw people to the circus, they’d parade down Main Street.

It was that prelude, the idea of anticipation, that ignited his obsession. His curiosity propelled him into research. He found out, for example, that the wagons were big and bright, often built and designed around themes. One, a Barnum and Bailey wagon called “The Hemispheres,” was so huge and heavy that when it accidentally hit a building in Chicago while turning a corner, the building collapsed.

And so —about 40 years ago — he crafted his first circus piece, a bright red, blue, orange and gold wagon he called “Homage to the Hemispheres.” It emulates that original monster vehicle, complete with one side each devoted to East and West, pulled by six horses, with two teamsters in bright red top hats and coats at the traces.

“At first I thought it was a complete piece,” he says. “But then years later, I thought, maybe it’d be good to have a few elephants.

“I kept looking at all the old photos, and the elephants usually have people riding on them, sometimes on carriages, so I made a few like that. And then I started putting clowns in because my dad was a clown.

“And then I wanted different kinds of elephants — trunks up because that’s the sign of a happy elephant, and that’s good luck. Then I wanted elephants with trunks down because some of them must have been sad. Then I wanted walking clowns. Then I realized somebody had to clean up after all those animals, so I created that little guy at the end with his wagon and shovel, picking up scat. “

He found photos of camels going down Saginaw Street in a circus parade sometime in the early 1900s — women bystanders in long skirts with hoops and bustles — and so he decided to try a few camels, researching the difference between the one-hump and two-hump varieties.

One thing paraded into another, so to speak, his love of the circus parade leading him back again and again to his process, back to his clay, back to his molds, back to his glazes, back to the kilns at Flint Institute of Arts where he continues to fire his colorful work.

“I’m not so interested in making a circus itself,” he says, noting that the mobile-maker Alexander Calder used to carry a miniature circus around with him in a suitcase.

“I’m interested in what comes before the circus. The idea of the parade is what absorbs me — what brings people to the event, the part that sets the stage, all the pieces that say, ‘come join us,’ the laughter, the fun, the promise of the exotic, the anticipation. I think a lot of life is like that, really — the anticipation. You can get so many hours of pleasure into working up to something — like Christmas, I suppose. And then the event itself is over so quickly.”

Custer makes it clear that his piece will be marked “Not For Sale” at Buckham. He has never been a “starving artist,” he notes, and he says he likes looking at his work. The parade, like much of his art, is still a work in progress.

And in fact, he says with a grin, he’s decided his parade needs some true-to-life scat, horse, camel and elephant. He’s researching what that should look like now.

Once he displayed several of his circus elephants at the Flint Art Fair. Somebody came up and said, “What do they do?”

Custer laughs. “They just sit there. They don’t have to do anything.”

But put into the circus parade, Custer’s elephants, camels, clowns, horses and band wagon are a feast for the eyes and spirit on a gloomy winter day.